Shooting the breeze with smart machines

Percept

December 2025

Dave Strugnell | February 2023

Alan Turing had a remarkable – and remarkably sad – life. A gifted mathematician, a brilliant codebreaker during the Second World War, a renowned contributor to the nascent post-war world of mathematical biology, a man both honoured (in the form of an OBE and Fellowship of the Royal Society) and persecuted by his government and society. His conviction in 1952 for homosexual acts led to “voluntary” chemical castration as an alternative to a prison sentence and ultimately to death by cyanide poisoning; whether by suicide or accident remains the subject of debate. It was a tragic end to a dazzling life.

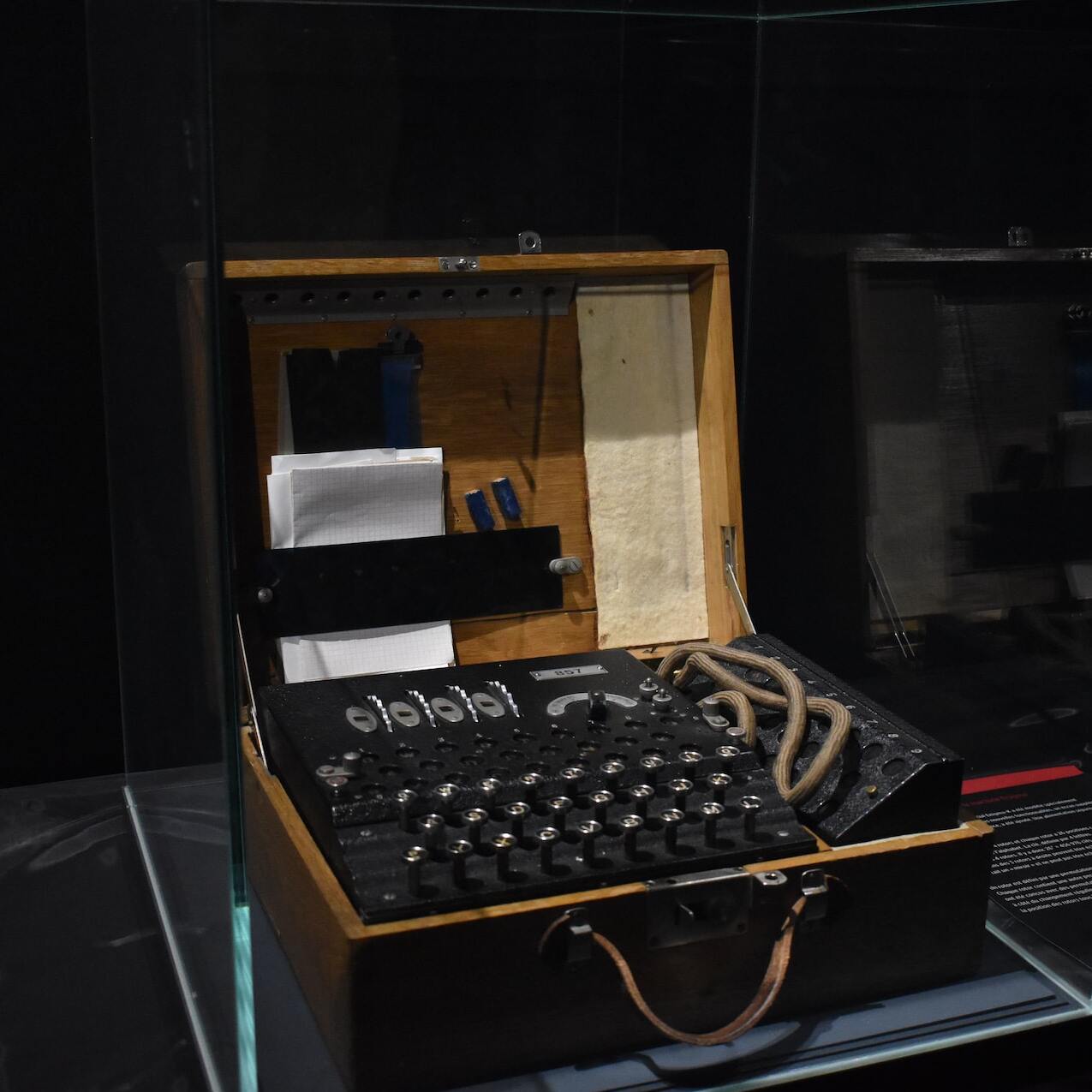

Turing’s legacy (which includes the 2017 UK legislation that retroactively pardoned those convicted under the earlier shameful laws being referred to as the “Turing law”) befits the intellectual colossus that he was: some of his proofs, including one made while still a Cambridge student, persist to this day in the canon of pure mathematics; his efforts in cracking codes set by the Enigma machine are widely credited as having been pivotal in swaying WW2 fortunes in favour of the Allies; he made profound original contributions in a number of areas of chemistry and biology; and he is today revered as a godfather of modern computer science, his work on computational logic and computability theory having provided much solid foundation for scientists of later years.

One of his enduring contributions was what we now know as the Turing Test, a method for evaluating progress towards Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) that is both productive and elegant in its simplicity. At a time in the early 1950s when there was much debate about how to construct a definition for whether machines could “think”, Turing proposed the following simple experiment: construct two rooms in which a person could converse electronically with an unseen respondent, in one room the machine and in the other a human, on the other side of a wall. If the person is unable to distinguish which conversation was with a human and which with the machine, then the machine has passed the Turing Test and can for all reasonable purposes be classed as intelligent.

I’ve been aware of the Turing Test for about 40 years, but interacting with ChatGPT is the first time that I’ve come close to feeling that a machine might actually pass it. Apart, of course, from the fact that ChatGPT isn’t trying to pose as a human; it’s pretty open about what it is if you ask it:

I am an AI language model known as ChatGPT, developed by OpenAI. My training corpus consists of a diverse range of internet text, including websites, books, and social media, totaling to over 40GB of text data. This large amount of data has allowed me to generate a wide range of responses and have a general understanding of many topics, making me well-equipped to respond to a variety of prompts.

And well-equipped it is. Once you’re done being wowed by the ease and clarity of its prose, you can begin to evaluate it on the usefulness of its responses. You might expect it be able to respond comfortably to Wikpedia-type questions that ought to be easy with that much training text data (my suspicion is that it’s orders of magnitude more than 40GB, but more on ChatGPT’s capacity for bullshit a little later). Ask it to tell you about what events gave rise to the First World War, or how butter is made, or why the sky appears blue to our eyes, and the AI will eat the question for breakfast. But where its developers have really pushed the boundaries in unprecedented ways is evident in its ability to extrapolate, to see beyond the narrow confines of the instruction, even, dare I say it, to be creative.

Ask it to write you a Twitter thread on the woes of loadshedding in South Africa, and it’ll come back with a serviceable suggestion (serviceable, that is, if you’re an opposition politician who’s having tea with the President later and doesn’t want to be overly strident, so you might want to ask it to rewrite using dark humour for a bit more fun). Ask it to come up with a plot outline for a Netflix series set in Durban involving a kleptomaniac monkey, an octogenarian chain-smoker and a pair of laddered stockings, and you’ll get some generic plot arc ideas that are unlikely to convince a Netflix producer without some serious additional work, but you’ll also get a solid starting point for your pitch and probably some moderately exciting hooks. Ask it to design the outline for an hour-long discussion about ChatGPT, as one of my colleagues who had that exact assignment did a couple of weeks ago, and it will happily do your work for you. Most astonishingly and usefully for me, ask it to write R or Python code to achieve some not entirely straightforward but not excessively complex task, and you’ll receive some code to cut and paste in less time than it takes you to think about making a cup of coffee, much less making it. It may not work perfectly, but chances are that you won’t have to change much, and it’s far easier than writing from scratch.

Cartoonists have asked it to create cartoons (in text form, obviously) and drawn the results. Teachers have used it to develop lesson plans. Podcast hosts have used it to suggest guests they should invite. Designers have used it in conjunction with Dall-E and Midjourney to design all manner of creations. Candidates have used it to anticipate interview questions. Somebody asked it to write their resignation letter, and it came back with career advice instead. And yes, predictably, students have used it to generate essays; I believe the smarter ones have then fed these through falsification software that alters structure slightly, swaps in the odd synonym and introduces a few deliberate spelling errors to make plagiarism impossible to detect (and I guess we’re going to have to rethink the definition of passing off someone else’s work as your own.) Just when you thought that teaching in the 21st century couldn’t get any harder…

Perhaps the biggest lesson I’ve learned about getting value out of ChatGPT is persistence. Don’t be satisfied with the first iteration of an answer. There’s always the ‘regenerate response’ button, but I find that modifying the request slightly, or giving some different steer, yields the best results. We tested this out recently by asking ChatGPT to write a headline for an article we wanted to write. It came back with something bland and uninspiring. So we asked it to try again with something sexier. The second response was better, but we wanted something harder-hitting and told the AI so. Now we were getting to responses we could live with, and after a final request to make it a headline that no reader would be able to ignore, we had something that we could work with (though being carbon-based life forms, we were still arrogant enough to think that we could improve it further ourselves).

And language appears to be much less of an obstacle than I had anticipated. Admittedly I haven’t tested its abilities to a great extent, but when I asked it, in Afrikaans, to describe actuarial science to someone new to the field, I got back a pretty reasonable response. And deploying three words that make up a depressingly high proportion of my very limited isiZulu vocabulary, I asked ChatGPT for its name: “Ngubani igama lakho?” To which it replied: “Igama lami ChatGPT. Ngingu AI model okulolu hlelo lwezilimi okwenziwe ngu-OpenAI.” (My name is ChatGPT. I am an AI language model developed by OpenAI.)

So is ChatGPT the vanguard of AGI? Well, it may yet prove to be, but we’re still some distance away from that (though sometimes in computing developments, large distances can be scaled in the blink of an eye; other times movement can be glacial). It certainly has limitations; read for example Ian Bogost’s article proclaiming that ChatGPT is dumber than you think (the first three paragraphs of which- spoiler alert here- were ChatGPT’s response to the prompt “Create a critique of enthusiasm for ChatGPT in the style of Ian Bogost”).

My most frustrating experience was using it to help me remember the name of a movie where all I had to offer by way of clue was that the main characters were a group of 12-year-old boys who are caught spying on the teenage girls next door using a drone, that being the sole scene that had survived in my leaky memory. After a dozen or so iterations, it felt to me that that the AI had suggested every movie but the one I was after. No, it didn’t star John Cusack… no, it was not set in London… no, they were not older teenagers, try again. And then, a single search string in Google got me to the title I sought immediately (‘Good Boys’, for what it’s worth).

I’ve also noted that ChatGPT, while in general being honest about its limitations, conscious of its role in society (it won’t tell you how to write ransomware or build chemical weapons – or so I’m led to believe, of course I’ve never tried) and disciplined in steering clear of controversy, has blind spots at the edges of its capabilities.

Notion is cornerstone software at Percept, and I’m frequently curious as to whether I can use it to achieve some goal. And almost certainly, ChatGPT will tell me that yes, I can do that in Notion, and proceed to give a description. I’ve had a few frustrating experiences of this kind, including one exhausting GroundHog Day exchange: it described to me how I would achieve my objective, including the formula that would be needed; I pointed out that a certain function it had used did not in fact exist in Notion; ChatGPT apologised to me (it’s nothing if not polite), agreeing that that function was indeed not a feature of the software and suggesting an alternative that included yet another non-existent function; and so on in a rather depressing ballet, until finally I accused it of making stuff up and forcing it to admit, sheepishly, or so I would like to believe, that perhaps it had not absorbed sufficient training data about Notion to be of any service.

The GPT in its name stands for the complex deep learning model pastiche that drives it, a Generative Pretrained Transformer: generative because it can generate new text based on the patterns it has learned from a large corpus of text data; pretrained because it has been trained on this data before being used for a specific task, such as answering questions or generating text; and transformer describing the architecture of the neural network model, which was first proposed by Vaswani et al. in 2017 and which has since revolutionised natural language processing. And as with any machine learning model, it is subject to the implicit bias inherent in the data on which it has been trained, although it seems that OpenAI have been careful to select training data as free as possible from explicit bias of the sort that most humans would find troubling. But if you’re trained on data from the internet, there is going to be a bias towards the thoughts and views of the highly-connected, economically-privileged world. Cassie Kozyrkov’s excellent outline of how this plays out for Midjourney is well worth a read, and ChatGPT won’t be free of this plague either.

On top of that, there are the general and ever-present risks of AGI. As a species, we are tasked this century with protecting our existence from an expanding catalogue of existential threats, climate catastrophe and nuclear disaster to name but two. Any move towards AGI brings with it risks and unintended consequences that we would be well advised to manage carefully (Will MacAskill has recently written eloquently on this in his masterful What we owe the future), but the competitive impetus for progress in this arena mitigates against that. Apart from the unpredictable, we face the spectre that even though ChatGPT won’t write malware for you now, future technologies built on similar foundations may not operate as ethically. Even now, ChatGPT could in principle be used, say, to improve the credibility of 411 scam and phishing emails and texts, with potentially dire consequences for victims. And there are many other deepfake text opportunities that I am insufficiently imaginative and devious to conceive of. The educational implications are obviously worth pondering – how will the way in which we teach and assess students have to change in the face of this technology? And if other people have had similar experiences to mine of ChatGPT’s apparent tendency to make things up rather than admit a deficiency of training data, then the potential for its use in flawed decision-making should have us all concerned; already, we’ve had the situation of a judge in Colombia basing his verdict in part of ChatGPT’s input.

Be that as it may, for now, I’m enjoying my daily interactions with the bot on a variety of topics, and taking its responses with a pinch of salt, though in truth I’m not throwing anything particularly consequential at it so there’s little at stake for me.

For how long though? Microsoft have invested many billions of dollars in OpenAI, despite Bill Gates’ early misgivings (he’s now a convert), specifically to secure this technology. Evidently they intend to make it the nerve centre of Bing, in a move that has some quaking in their Google boots, although perhaps Sundar Pichai will be reassured by my ‘Good Boys’ anecdote. Full unrestricted access may soon be available for a subscription of over $40 a month, putting it out of the reach of the majority of us, although it seems there will still be a poor second cousin available for free, on slower, more crowded servers with rationing of questions.

It’ll be a great pity when it goes, but hardly unexpected given the economics of running the architecture. We function in a global economic order, after all, in which monetisation of good ideas is almost always the end goal, and that’s how we have ended up with the great societally harmful mess that is social media in 2023…

I’ll keeping chatting with ChatGPT while it lasts, and I’m not holding my breath that the machine will offer anything useful when I ask it – as I will soon surely have to – “How do I find a workaround to access you without paying the exorbitant fee your bosses demand?”